Part 1: Family Medicine at Duke - Fourth Time's a Charm

Editor's Note: This is the first in a seven-part series about the history of family medicine at Duke University Medical Center.

Read Part 2 | Read Part 3 | Read Part 4 | Read Part 5 | Read Part 6 | Read Part 7

In the spring of 1985, the fate of the Department of Community and Family Medicine was in doubt after William Anlyan, M.D., then-chancellor of health affairs for Duke University, announced that all clinical operations of the department would be phased out, including the family medicine clinical practice and residency program.

Anlyan told E. Harvey Estes, Jr., M.D., then-chair of the department, about his decision in a closed-door meeting on April 2, 1985. Estes submitted his letter of resignation the next day.

What followed was a very public struggle between Duke University Medical Center, Durham County General Hospital, family physicians from across the nation, Duke medical students and alumni, and national family medicine organizations.

It wasn’t the first time the department had to fight for family medicine, though, and it wouldn’t be the last.

Origins of the department

When the Department of Community Health Sciences — the original name of the department — was founded in 1966, subspecialty departments in the medical school were against the creation of a family medicine program in the medical center.

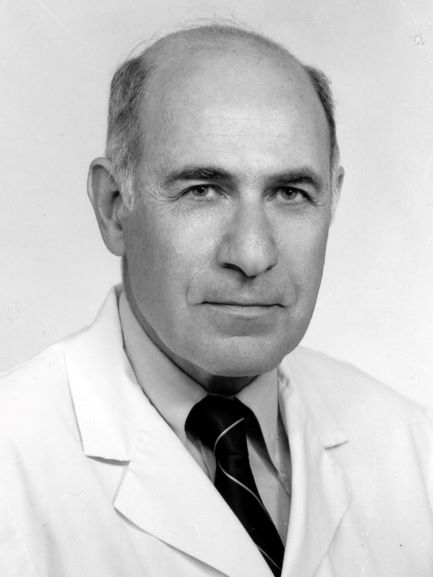

In a recent interview, Estes, distinguished service professor emeritus of community and family medicine and original chair of the department, said the Department of Community Health Sciences was formed out of political necessity. He said Duke was feeling political pressure to meet the needs of rural North Carolina and generalist physicians all over the state.

Estes, 91, said that Duke received a fair amount of state money for meeting state needs, and that money was under threat because of Duke’s apparent insensitivities to what the state needed.

“So in the face of this increasing pressure, [Duke medical center leaders] were asked to consider starting a department of family medicine, which they were vehemently opposed to,” Estes said. “It was against their principles. It was against their sense of pecking order. It was the bottom of the pecking order, and they were the top.”

In a recent interview, Joseph Greenfield Jr., M.D., James B. Duke Professor of Medicine and former chair of the Department of Medicine, agreed that at the time, the subspecialists at Duke did not want anything to do with the newly formed department.

“The attitude of most of the subspecialists was, ‘Duke Hospital is a subspecialty endeavor. It is not primary care, we don’t want to have a damn thing to do with primary care and it shouldn’t be at Duke medical center,’ ” Greenfield recalled.

The reaction at Duke to the possible formation of a family medicine program wasn’t an anomaly at the time. The medical profession had increasingly become more focused on specialties since the standardization of medical education in the early 1900s by the American Medical Association.

General practitioners had become lower rank and smaller in numbers and there was a lot of animosity between specialists and general practitioners. The article “The History of Family Medicine and Its Impact in US Health Care Delivery” stated that general practitioners “continued to lose ground as they were prevented from hospital work, procedures and other activities.”

In 1966 a proposal was submitted to Duke for sponsorship of a family medicine program, but was rejected by the Medical School Advisory Committee. A 1975 document from the Duke University Medical Center Archives stated that “Duke was found to be an unfriendly environment for the development of a family medicine program as the department began in 1966.”

Estes said that the other clinical department chairs suggested that instead of a family medicine department, they could create a department that looked at sociology, economics, teams and computers. Thus, the Department of Community Health Sciences began in July 1966 without a family medicine program.

Fourth time's a charm

The Department of Community Health Sciences had multiple office locations in its early years. The first were in the rear of a hotel on Erwin Road, just beyond the Durham VA Medical Center, then later at the Marshall I. Pickens Building, then on the bottom floor of what is now Trent Hall.

Additional offices were also located on the grounds of Watts Hospital, which operated as a hospital for the white community on Broad Street in Durham from 1895 to 1976. Department activities were housed there in support of community physicians.

In the late 1960s, Watts Hospital was operating residencies in pediatrics, medicine and surgery, and, according to Estes, were all doing poorly.

“They could not recruit,” Estes said in a recent interview. “They were largely filled with foreign-trained medical graduates. Some of these were non-English-speaking when they got here.”

Estes said that as a result of his department’s Watts Hospital offices, his faculty and staff started to form close working relationships with the Watts faculty and staff. The Department of Community Health Sciences taught a course in medical English for the Watts residents and Estes also hired two people to be assistants to the Watts staff to help link them to Duke’s medical center.

During this time, it had become apparent to Estes that the department needed to be training physicians, specifically family physicians, who could go to small communities in the state to practice medicine and spend their entire lives there taking care of the people who lived in those communities.

“If you are going to a little burg in the northeast corner of the state, the only people that can make a living with a clinic of this sort are going to be family physicians who are omni-capable,” Estes said. “They are capable of doing obstetrics, capable of doing minor surgery, capable of treating children, capable of treating old people. So a generalist physician was needed.”

But a second attempt, in 1970, to create a family medicine program within the department was also rejected by Duke. According to a 1975 Duke University Medical Center Archives document, “The faculty again did not favor the addition of a family physician training program at that time.”

With the failures of the Watts residencies and the resistance he had received from Duke, Estes saw an opportunity. He spoke with the then-chief of medicine at Watts, Edward Williams, M.D., and proposed a solution to both of their problems.

“We went to Ed and said, ‘Ed, which would you rather have: no residency, or would you rather have a family medicine residency?’ Estes recalled. “Family medicine was brand new; there were no family medicine residencies. This was an idea that was being pushed nationally, but had not come to fruition. Not in the South, at least.”

“Ed began to plot with us to get a family medicine residency because he was sick of putting together a residency and having all the fuss and bother and then having a group of residents that he didn’t consider top flight,” Estes said.

In 1971, Watts Hospital merged with the newly formed Durham County Hospital Corporation. Williams presented the family medicine residency proposal to the hospital corporation and it was approved. Estes said they then took the proposal to Duke and were turned down once again.

“We … did a little more homework and a little more political work, and a year later went back with a second proposal,” Estes said. “It was approved in both places.”

After this fourth attempt, the Duke-Watts Family Medicine Residency Program and the department’s Division of Family Medicine began in 1972.

A 1975 document from the Duke University Medical Center Archives stated: “In conjunction with Watts Hospital, and with the vigorous support of Dr. Edward Williams, the Chief of the Medical Service at Watts, plans gradually evolved for a Family Medicine Program, as a joint endeavor between the Department and Watts Hospital.”

The document also stated: “The Family Medicine Program has added a very useful clinical focus to the activities of the Department, and the program now offers a new and much needed role model for the Duke medical student.”

A thriving practice

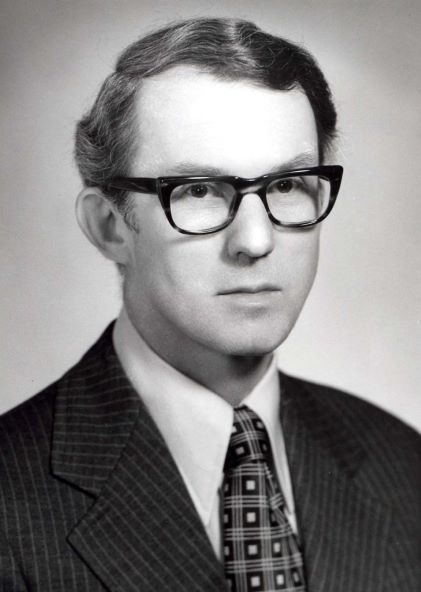

Estes said in a recent interview that the Duke-Watts Family Medicine Residency Program was highly successful as an educational program and also as a clinical practice. He cited the hiring of William J. “Terry” Kane, M.D., as the single most important factor in its success. Kane succeeded Lyndon Jordan, M.D., who led the program for about a year.

Estes, distinguished service professor emeritus of community and family medicine, said Kane came recommended to him by a colleague at a family medicine program in Rochester, N.Y. Kane was a recent graduate of family medicine residency himself and was described as a natural leader.

Estes said that Kane brought with him a very able administrator, David Hunter, and together they were effective in gaining financial support from available state and foundation sources, in addition to attracting superb residents.

“Terry wouldn’t take no for an answer,” Estes recalled. “Terry was like a bull in a china shop; you either disliked him intensely or you loved him. Most people loved him.”

In 1976, Durham County General Hospital opened, merging Watts Hospital and Lincoln Hospital, which had served the African-American community in Durham. The Duke-Watts Family Medicine Residency Program relocated to the grounds of Durham County General Hospital in a new, state-of-the art building that was constructed with money raised by the department. Estes said it was a combination clinic-teaching site with the residency program and the Duke-Watts Family Medicine Center.

“The family medicine residents all had their clinical space there, and they saw their patients there,” Estes said.

Kathryn M. Andolsek, M.D., MPH, professor of community and family medicine and assistant dean of premedical education in the Duke University School of Medicine, became the director of the Duke-Watts Family Medicine Residency Program in January 1985. She said that by 1985 the program had 39 residents and a fellowship.

“We were a very hot commodity in terms of residency programs,” Andolsek said. She added that the practice was thriving with about 50,000 patient visits in a year, had weekend and night hours, and did nursing home care and home visits. “It was a very kind of cradle-to-grave family medicine experience.”