Duke Physician Assistant Program: The birthplace of the physician assistant profession

The Duke Physician Assistant Program celebrated its 50th anniversary in October 2015, marking the milestone of being the first physician assistant (PA) program in the nation and the birthplace of the PA profession.

The Duke PA program originated in the Department of Medicine, but moved to the Department of Community Health Sciences (later renamed the Department of Community and Family Medicine) two years later.

PAs practice medicine on health-care teams under the supervision of physicians and surgeons. They examine patients, diagnose injuries and illnesses, and provide treatment. The physician assistant profession is one of the fastest-growing in the nation and was ranked the most promising job of 2015, according to Forbes.

The Duke PA program has consistently been ranked one of the top programs in the nation, and currently is ranked No. 1 by U.S. News & World Report. There are 179 students in the program this year — 91 in the first-year class, and 88 in the second-year class.

Pat Dieter, MPA, PA-C, professor of community and family medicine and division chief of the Duke Physician Assistant Program, says that students who come to the Duke PA program make tremendous sacrifices to attend, including traveling across the country and relocating families.

“It’s not a matter of convenience at all for our students,” Dieter says. “It’s people making major life changes in order to come here.”

It’s not lost on students that they are attending such a historic program, says Karen Hills, MS, PA-C, associate professor of community and family medicine and program director of the Duke PA program. Hanging on a wall in the PA program building at 800 S. Duke St. in downtown Durham are photos of all the graduates of the program — starting with the first three who graduated on Oct. 6, 1967.

“When [students] … walk down the hall and they see those … three pictures, and then there’s a few more pictures,” she says. “And then they walk around and they’re like, ‘Oh, my gosh. My picture’s on the wall with all of these pioneers of the profession; all the people who did these things for the first time.’ I think … that begins to kind of hit home a little bit.”

In the beginning

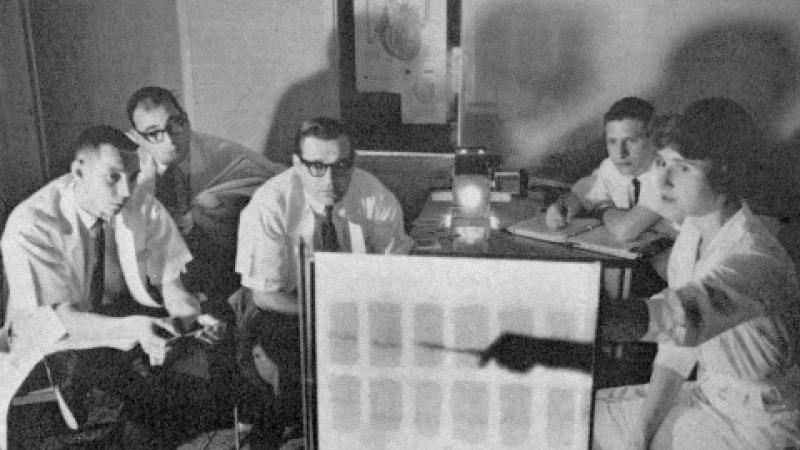

The PA program at Duke began in October 1965 when Eugene A. Stead, Jr., M.D., then-chair of the Department of Medicine at the Duke University School of Medicine, began a two-year curriculum to train people to fill a gap between physicians and nurses, and expand the prior education and experience of ex-military corpsmen.

There was a nursing shortage during this time, according to E. Harvey Estes, Jr., M.D., professor emeritus, Duke University School of Medicine, and former chair of Duke Community and Family Medicine. He says that skilled individuals were needed to assist in the laboratories and with medical procedures at Duke University Medical Center.

Estes says that Stead recognized this gap needed to be filled and turned to his division chiefs and colleagues to help him solve the problem.

“He wasn’t the only one that had these innovative thoughts,” Estes says. “He had a lot of young people working with him that had their own ideas that he … supported.”

Estes says Stead and Henry McIntosh, M.D., head of Duke’s cardiac catheterization lab and coronary care unit, put their heads together to identify the best candidates to train for this new role.

“They looked at the employment structure around Durham and they said, ‘OK, what about firemen? Firemen work and they’re smart and they can learn to do things. … Many firemen work three days a week and then they’re off. Maybe we could recruit firemen to come in and do this.’ And they did that,” Estes says.

However, Estes says that because of the irregularity of the firemen’s schedules, this idea did not ultimately work. McIntosh and Stead then looked at the possibility of bringing former military corpsmen into this role. Some of McIntosh’s former medical students who had been in the Navy were successfully running laboratories in various Navy centers across the country, according to Estes.

This idea led to the recruitment of four former Navy corpsmen to comprise the first class of Duke PA students. Three of these students — Kenneth F. Ferrell, Victor H. Germino and Richard J. Scheele — completed the program.

In a letter dated Sept. 24, 1964, Stead stated the following about developing the PA program.

“The Department of Medicine of Duke University Medical Center is establishing a program to create a new position in the health field. We have chosen to call these individuals ‘physician-assistant.’ We believe there is a need for males to be committed to the health field to fill a gap between the physician and the nurse. This gap cannot be filled by additional training for nurses because nurses are already in very short supply.

“These individuals will become skilled in many areas of the medical profession, such as general patient care, intravenous therapy, cardiac resuscitation, respiratory care, catheterization of the bladder, lumbar puncture, paracentesis, gastric and intestinal intubation — to name just a few. They will be capable of extending the arms and brains of the physician, so that he can care for more people. They will work under physician supervision in the home, the clinic, the hospital, and in specialized medical care units.”

Stead modeled the physician assistant role after Henry Lee “Buddy” Treadwell, an assistant to Amos N. Johnson, M.D., in a medical clinic in Garland, N.C. Treadwell and his work as an assistant to Johnson were well-known at Duke University Medical Center and to Stead, and Treadwell is widely regarded as the “prototype PA.”

A commitment to diversity

Lloyd Michener, M.D., professor and chair of Duke Community and Family Medicine, says the Duke Physician Assistant Program has always had a focus on diversity.

“Because diversity alone is worthwhile, but also because we know that diverse groups come up with better solutions,” he says.

The program graduated its first African American student, Prentiss Harrison, in 1968. Harrison was the first African American PA in the country. According to his biography on the Physician Assistant History Society website, Harrison was instrumental in educating African American physicians about the PA concept.

Originally, the PA program was intended solely for training men. However, in 1970, Joyce Nichols became the first female graduate of the program, in addition to being the first female African American graduate and the first African American woman to practice as a PA.

It was because of Nichols’ persistence that women were allowed admittance to the program. Nichols was working as a licensed practical nurse at Duke when the PA program began. Estes says that Nichols began to push PA program administrator Jim Mau to allow her in the program.

“Joyce continued to prod Jim Mau, and Jim Mau prodded Gene Stead. … Sooner or later, she prevailed,” Estes says.

Today, the first-year class of Duke PA students consists mostly of women — there are 66 female students and 25 male students.

Eugene Stead as a teacher and innovator

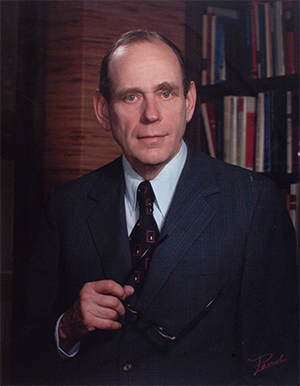

Estes says he first met Stead in 1945 when he was a medical student at Emory University, where Stead was the dean and professor of medicine.

“He was feared, and he was respected, and he was loved at the same time,” Estes says. “Everybody revered him, because he genuinely cared about your education and about you.”

“He taught at the bedside; continued to do that all of his career,” Estes says. “He never would sit down in a conference room in a formal setting and say, ‘I’m going to talk about typhoid fever today.’ It was always … ‘What can we learn from this particular patient?’ ”

Estes says that Stead was the only person — not just at Duke, but across the nation — who could have started this program and launched the PA profession.

“No one anywhere could have gotten this done. Anywhere,” Estes says. “Here is a man who is renowned in the medical world, trained more people that went along to become professors … than anyone else at that point … and his authority carried a long way. And his authority was not just at Duke; his authority was nationwide. So it’s just damn fortunate that he was here and felt as he did.”

In 1967, just two years after the program’s founding, Estes, who had been named chair of the newly created Department of Community Health Sciences in the School of Medicine, assumed responsibility for the PA program. At this time, Stead had stepped down as chair of the Department of Medicine and took a sabbatical from Duke.

The PA program became part of the Department of Community Health Sciences and has been housed within that department — later renamed the Department of Community and Family Medicine — ever since.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Estes was a staunch supporter of PAs, writing articles, chairing or serving on advisory committees, and traveling extensively to promote the concept of PAs.

“I’m proud of the PA profession,” Estes says. “I think it’s going to be the biggest innovation in medicine in my lifetime.”

The pairing of the PA program with the department in 1967 was brilliant, according to Michener. He says the department was founded to make a difference in communities through innovation, and the PA program, itself being new and innovative, has been focused on partnering with practices to bring in health care providers to make a difference.

“The two feed on each other,” Michener says about the department and the PA program. “One’s focused on training and one’s focused on innovation. I think the department — and the field — has been driven by that combination.”

Looking ahead

Michener says that over the next 50 years, the scope of physician assistants’ work is going to broaden and students will have more options than they had before. He says that because of a shift in care delivery that is more focused in the community, there will not be enough doctors. However, he says that even if there were enough doctors, that wouldn’t be the answer.

“We’re going to need much more comprehensive team models from the community side,” Michener says. “And we’re going to need PAs in all those settings.”

Dieter agrees. “The skills of the provider are going to need to change,” Dieter says. “PA education has been very flexible and the model of PA practice has been very flexible. So I think that … we need to support the change in the health care system.”

“I think it’s on a good path,” adds Estes. “We’ve got to make sure that they continue to do one thing well … and that’s train the PAs to take care of a person who needs care and taking responsibility of getting them that care they need.”

PA profession by the numbers

Source: 2014 Statistical Profile of Certified Physician Assistants

- 101,977: Number of certified PAs in the nation

- $98,387: Average salary of PAs

- 66.6: Percentage of PAs who are female

- 16: Percentage of PAs who were female in 1974

- 26.4: Average number of months PA programs last

- 196: Number of PA education programs in the U.S.

- 262: Projected number of PA education programs in the U.S. by 2019

Kenisha Syphertt contributed to this report. Story originally published Sept. 28, 2015.