50th Anniversary: Origins of the Department

In July 1966, the Duke University School of Medicine established a new department: the Department of Community Health Sciences. Its roots were multiple and complex, and began with a decision to discontinue another department — the Department of Preventive Medicine — which had functioned since the first days of the medical school.

The Department of Community Health Sciences (renamed Community and Family Medicine in 1979) has long been described as a “catch all,” a department that took in divisions and programs that didn’t belong anywhere else in the medical center, said George R. Parkerson, Jr., M.D., professor of community and family medicine and former chair.

“Anything they couldn’t find a place for in the medical center they put into the department,” Parkerson said.

July 2016 marks the 50th anniversary of the department’s founding, and through the years the seemingly mismatched programs and divisions have worked together toward one common goal: improving the health of people in their communities, whether at home, at work or in the local community.

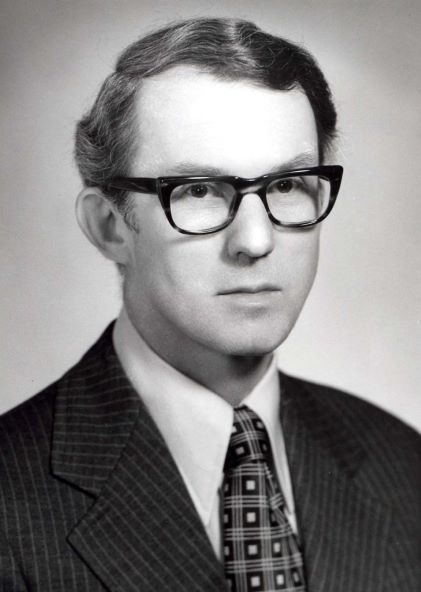

Original chair E. Harvey Estes, Jr., M.D., distinguished service professor emeritus of community and family medicine, said in a recent interview that current employees of the department should be very proud of where they work.

“They are members of the most important department in the medical school,” Estes said. “Our department will never make a lot of money … . We’re doing things that no one else wants to do, that nobody else realizes is important.”

Today marks the 50th anniversary of the department’s founding, and current and former faculty, staff, residents and students gathered on June 28 to celebrate the milestone. Estes and Parkerson spoke at the event, in addition to current chair J. Lloyd Michener, M.D., and Viviana Martinez-Bianchi, M.D., FAAFP, assistant professor of community and family medicine and director of the Duke Family Medicine Residency Program.

Origins of the department

According to a 1975 document from the Duke University Medical Center Archives, prior to the formation of the department, preventive medicine and public health were taught in the early years of the Duke University School of Medicine, with an emphasis on public health and sanitization problems, including the preservation of sanitary water, milk and food supplies, and the investigation of infectious-disease epidemics.

Faculty gave lectures and conducted laboratory exercises, with assistance from the state and county boards of health and visiting lecturers from The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s then-School of Public Health.

In 1964, a Department of Preventive Medicine was established, with David T. Smith, M.D., as chair. The department taught epidemiologic principles, environmental factors in health and illness, illness care in the family environment and international health problems.

In 1965, as Smith was retiring, a faculty committee was appointed to study the future role of preventive medicine in Duke’s curriculum and to examine the future of the Department of Preventive Medicine.

According to a document from the Duke University Medical Center Archives, “There was a widespread feeling, not only at Duke, but also throughout the country, that sanitation and public health topics were no longer worthy of large blocks of curricular time, and that most aspects of preventive medicine should be interwoven with pediatrics, internal medicine, psychiatry and other clinical teaching.”

The committee examining the future of preventive medicine concluded that the successor department should have a broader role. It would focus on groups of patients, the organization and delivery of health care and access to health care, and would utilize diverse disciplines such as economics, social sciences, computer sciences, biostatistics and epidemiology.

In an article in Intercom, a publication of the Duke University Medical Center, about the founding of the new department, William Anlyan, M.D., then-dean of the School of Medicine, stated “Our aim is to create a new physician — one who will bridge the gap between the exciting advances being made at the research level of medical sciences and their application at the family and community level.”

Naming a department chair

Estes, a cardiologist, was recruited from the Department of Medicine to lead the new Department of Community Health Sciences. Estes, a professor of medicine, was recognized as an outstanding cardiologist and cardiovascular physiologist in electrocardiography. He served as the president of the North Carolina Heart Association in 1965 and was involved in other statewide programs and organizations through the 1950s and ’60s.

Estes said that he was probably suggested for this role by Eugene A. Stead, Jr., M.D., then-chair of the Department of Medicine, who was head of the search committee to find a chair for the newly created department, because of his involvement in various statewide organizations and his familiarity with the medical leaders in the state.

Estes said that Stead’s opinion was that even though Estes was a cardiologist, he would be able to lead this new department and do it well. Estes said that he grew up in a town of less than 200 people in Georgia that had one family doctor who delivered him in the home, thus he valued family and community doctors and understood the need to extend health care services to isolated communities.

Early programs

According to a document from the Duke University Medical Center Archives, the department was “one of the first such departments in existence in the United States. There were, as a result, very few models which could be used for patterning a program. There were no textbooks, and no journals relating to community health. There was also no training program in this discipline, and no source of previously experienced faculty.”

Limited access to medical care was one of the first problems this department identified and targeted. Toward this effort, in 1967 the department’s computer program, under the direction of Howard K. Thompson and W.E. Hammond, began to explore the use of a computer-generated medical history and computer supported data systems.

“We started our own computerized medical record,” Estes said. “We were then five years ahead of anybody.”

And the Physician Assistant Program — having been founded by Stead in the Department of Medicine in 1965 — joined the Department of Community Health Sciences in 1967. This program focused on new types of workforce to address the problem of access to care. Estes assumed responsibility for the PA program in 1967 when Stead took a sabbatical from Duke.

In 1968-69, the department began establishing clinics throughout Durham County, utilizing community health workers and physician assistants. And a program in occupational medicine, led by Leonard Goldwater, M.D., began in 1968.

Political pressure

In a recent interview, Estes, said the department was formed out of political necessity. He said at the time the department was founded Duke was feeling political pressure to meet the needs of rural North Carolina and generalist physicians all over the state.

Estes said that Duke received a fair amount of state money for meeting state needs, and that money was under threat because of Duke’s apparent insensitivities to what the state needed.

“So in the face of this increasing pressure, [Duke medical center leaders] were asked to consider starting a department of family medicine, which they were vehemently opposed to,” Estes said. “It was against their principles. It was against their sense of pecking order. It was the bottom of the pecking order, and they were the top.”

Joseph Greenfield Jr., M.D., James B. Duke Professor of Medicine and former chair of the Department of Medicine, agrees that at the time, the subspecialists at Duke did not want anything to do with the newly formed department.

“The attitude of most of the subspecialists was, ‘Duke Hospital is a subspecialty endeavor. It is not primary care, we don’t want to have a damn thing to do with primary care and it shouldn’t be at Duke medical center,’ ” Greenfield recalled in a recent interview.

The reaction at Duke to the possible formation of a family medicine department wasn’t an anomaly at the time. The medical profession had increasingly become more focused on specialties since the standardization of medical education in the early 1900s by the American Medical Association.

General practitioners had become lower rank and smaller in numbers and there was a lot of animosity between specialists and general practitioners. The article “The History of Family Medicine and Its Impact in US Health Care Delivery” states that general practitioners “continued to lose ground as they were prevented from hospital work, procedures and other activities.”

Between 1966 and 1970, two separate proposals were submitted to Duke for sponsorship of a family medicine program, but both were rejected by the Medical School Advisory Committee.

A 1975 document from the Duke University Medical Center Archives states that “Duke was found to be an unfriendly environment for the development of a family medicine program as the department began in 1966. This matter was again discussed in 1970, and the faculty again did not favor the addition of a family physician training program at that time.”

Estes said that the other clinical department chairmen suggested that instead of a family medicine department, they could create a department that looked at sociology, economics, teams and computers. Thus, the Department of Community Health Sciences began in July 1966.